This post is meant to be a reference on the minimum wage. It is an ongoing project and will be updated as new topics, new questions, and new data arise. There are many more topics regarding the minimum wage that I will add in the future. This post is quite long so I created a table of contents that links to each section. Feel free to skip to topics that you are particularly interested in. I may use some of the information in this post to make more specific posts that elaborate on each topic. The intention of this post was not meant encourage or discourage the minimum wage, but rather provide some historical background and data. At some point I will create a separate post with my thoughts on the minimum wage and what aspects of it I support while also highlighting some of it’s limitations.

If you have any questions about the topics covered, if anything is particularly unclear, or if you think I have missed something, please leave feedback using the email form at the bottom of the page (click the email address to access the form). Additionally, to interact with the graphs on the page you may need to double click the graph to activate the content.

↓More↓

- Introduction

- A Brief History of the Minimum Wage and How it Works

- Adjusting the Minimum Wage for Price Inflation

- Adjusting the Minimum Wage for Productivity

- FAQ: What effects do raising the minimum wage have on the economy?

- Does the minimum wage increase prices?

- Does the minimum wage lead to higher unemployment?

- “Minimum wage workers are mostly high school and college students. They don’t need $15 an hour!”

- “I am alright with raising the minimum wage but $15 an hour is too high!”

- Does the minimum wage reduce income inequality?

- Do increases to the minimum wage lead to higher wages for non-minimum wage workers?

- Well, if it raising the minimum wage is so good, why not raise it to $100 an hour?

Illinois is Set to Raise the Minimum Wage to $15 an Hour

As a resident of the state of Illinois, I have been keeping up with the recent news regarding Illinois raising the state minimum wage to $15 an hour by 2025. A bill to increase the state minimum was recently signed into law by Govenor J.B. Pritzker after passing the state legislature. Illinois will join 4 states and 4 cities nationwide in incrementally raising their minimum wage to $15 an hour.

As a result, many Illinoisans have re-joined the debate on raising the minimum wage. As with many public policies regarding economics, there is much debate on what the effects this increase might have on workers, businesses, and the economy as a whole.

My goal of this post is to bring context to the minimum wage discussion by providing a short history of the minimum wage, highlighting trends in the minimum wage since its creation, and respond to common questions/concerns on its effects on the economy. There is a lot of disagreement in the empirical literature on the minimum wage. Many studies’ results conflict with one another and many times the results are so nuanced that they are difficult to compare. That being said, I try to compare and analyze the results from as many angles and perspectives as possible in order to get a better feeling of the pros and cons of the minimum wage.

A Brief History on the Minimum Wage and How it Works

The minimum wage was enacted by President Franklin Roosevelt in 1939 under the Fair Labor Standards Act following the implementation of his set of socioeconomic policies referred to as The New Deal.

The 60 years preceding the Great Depression in 1929, the United States went through a significant industrialization period where markets encouraged workers to pursue jobs in large urban industry instead of agrarian smaller business. As these businesses grew larger and hired greater amounts of workers, the greater the control the business owners had over workers. The employers were able to make larger amounts of profit at the expense of the wages of the workers.

As time progressed, the workers made such meager wages that they were then unable to spend much money as consumers. This lead to employers laying off more workers, which created greater competition among the workers for a smaller amount of jobs. This gave the employers even more power to pay the workers less than the value they produced for the company. There was no limit to how little the employers were willing to pay their employees, just whatever little amount that the desperate workers were willing to accept. This process continued until the workers could not purchase the products that they themselves produced, leading to the Great Depression. The ability for employers to pay their employees minuscule wages in order to create greater profit led to some serious economic consequences.

In response to the worker commiseration from the Great Depression, the Roosevelt administration implemented many economic policies during and after the New Deal in order to help resist the tendency of private business to drive down wages. One method of resistance was through having a legal floor on how low employers can pay their employees through the minimum wage.

When F.D.R. announced his plan for the minimum wage in 1933, he clarified what he intended his proposal for the minimum wage to be in his public statement on the National Industrial Recovery Act.

…[N]o business which depends for existence on paying less than living wages to its workers has any right to continue in this country. By “business” I mean the whole of commerce as well as the whole of industry; by workers I mean all workers, the white collar class as well as the men in overalls; and by living wages I mean more than a bare subsistence level-I mean the wages of decent living.

-President Franklin Roosevelt (1933, Statement on National Industrial Recovery Act)

From this statement, F.D.R. made clear that the purpose of the minimum wage wasn’t to sustain a life of mere existence, but to support a decent living.

Through many factors, such as the New Deal and the large public spending during World War II, workers had more jobs and higher wages. This allowed workers to purchase more goods and services, which lead to higher sales, more jobs, and even higher wages.

Adjusting the Minimum Wage for Price Inflation

Before we explore the historical trends of the Minimum Wage, we first must distinguish the nominal minimum wage from the real minimum wage. The nominal minimum wage is the dollar amount that was legally documented each time it was revised or increased. For example, in 1968 the minimum wage as written in law was $1.60 an hour. However, $1.60 in 1968 was worth a lot more than $1.60 now. As time has passed, inflation has changed the value of goods, services, and money. As with most historical economic data, we must adjust the nominal minimum wage amounts for inflation. This new inflation-adjusted figure is the real minimum wage.

(Red Line = Real Federal Minimum Wage (in 2017 $, using CPI-U), Pink Line = Real Federal Minimum Wage (in 2017 $, using CPI-U-RS), Grey Line = Nominal Federal Minimum Wage (in current $). Nominal minimum wage data is from the Department of Labor. Inflation data (CPI-U) is from Bureau of Labor Statistics with nominal minimum wage to calculate the real minimum wage (in 2017 $, using CPI-U). For the real minimum wage (in 2017 $, using CPI-U-RS) data, I used the Economic Policy Institutes data.

The minimum wage has fluctuated in an inverted U-shape since its creation. The interactive graph above shows this. When the minimum wage was first implemented in 1938, it was set at 25 cents. In 2017 dollars, that is approximately $3.80 – $4.35. The real minimum wage continued to increase until 1968, where it reached about $9.9-$11.27 an hour (in 2017 dollars). It has then decreased to our current federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour. This means that minimum wage workers are being paid about 27-36% less per hour than they did 50 years ago. One common response to this data above is “What if they deserve less than they did 50 years ago? What if they just don’t work as hard?”. Are workers more or less productive now than 50 years ago?

Adjusting the Minimum Wage for Productivity

Ever since data has been made available in the U.S. on the productivity of workers , research has shown that workers have consistently increased their productivity. From 1947 to the 1980s, the wages in general were closely tied to worker productivity. As worker productivity increased, so did their wages. The more products and services the workers created, the more their income was increased. From the 1980s onward, wages have decreased while hourly wages have flattened. This relationship between productivity and average wages is demonstrated in the graph below.

Double click the graph below to activate the interactive data visualization.

A similar trend has occurred with the minimum wage. From 1947 to the 1980s, the minimum wage grew along with worker productivity. From the 1980s onward, worker productivity continued to increase while the real federal minimum wage has decreased. The graph below shows what the federal minimum wage would have been if it was adjusted for productivity.

Double click the graph below to activate the interactive data visualization.

This means that even though workers have become more productive, they are not receiving compensation for the additional value of their increased productivity. If the minimum wage continuously increased and kept up with worker productivity, the minimum wage for 2017 would be $19.33. Instead, this money from the workers productivity has gone to their employer and business investors. This highlights an antagonistic relationship between workers and employers: the less compensation the owners pay their workers, the more the owners of businesses are able to profit. The lower the minimum wage, the less businesses have to spend on labor and the more they can keep to give to investors, reinvest in their businesses, give to CEOs, administrators, managers, and financiers. Since CEOs, administrators, managers, and financiers are common professions among the top 1% earners category, I created the graph below to compare the top 1% earners incomes with the real minimum wage. This graph shows an inverse relationship between the minimum wage and top 1% earners.

Grey Line = Top 1% Earner’s Share of National Income (in 2014 dollars), Red Line = Real Minimum Wage (in 2017 $, CPI-U). Nominal minimum wage data is from the Department of Labor. Inflation data (CPI-U) is from Bureau of Labor Statistics with nominal minimum wage to calculate the real minimum wage (in 2017 $, using CPI-U). Top 1% income share data from Piketty et. al 2017.

FAQ: What effects do raising the minimum wage have on the economy?

In response to the steady decrease in the real minimum wage, social movements have began to organize for significant increases to the minimum wage. In 2012, the Fight for $15 movement began when fast food workers in New York city organized to demand an increase in the minimum wage in New York to $15 an hours plus and improvements to union rights. Since then four states (New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, California) and four cities (Washington D.C., Portland, Seattle, and San Francisco) have raised their minimum wage.

At the same time, attempts to prevent, reduce, and even eliminate the minimum wage have emerged as well. The city of St. Louis in 2017 passed a city ordinance establishing a $10 minimum wage above the state of Missouri’s minimum wage of $7.70. Shortly after implementation, the Missouri legislature and Governor Eric Greitens passed and signed a bill that overrode the newly established $10 minimum wage, bringing it back down to $7.70. The governor sited concerns about job loss as the rational for preventing the new minimum wage. Some lawmakers have remained strongly critical of increases to the minimum wage due to concerns about job loss, automation, inflation, and the ability for small businesses to afford the increases. Some lawmakers have even advocated for the elimination of the minimum wage altogether.

It is clear that raising the minimum wage is a contested topic. Some argue that the inflation has eaten away at the the minimum wage, that it has become unlivable and must be significantly increased. Others argue that significant increases could decrease the number of jobs and increase the cost of prices and therefore should not be increased, or even possibly lowered. What are the actual effects of the minimum wage?

Does the minimum wage increase prices?

Short Answer: Increases to the minimum wage increase prices very slightly, but significantly less than the increase to the minimum wage. On average, for a 10% increase to the minimum wage, there is less than a .4% increase in prices.

Long Answer: A common concern regarding increasing the minimum wage is whether or not it increases prices of products and services. The concern comes from the idea that if goods and services are created from peoples labor, that an increase in the cost of their labor through increasing the minimum wage would lead to more costs for businesses. This would lead businesses to raise the price of their products and services in order to be able to pay for the workers. The conclusion people often come to is that the increase in prices would negate the increase to the minimum wage, thereby making it a pointless effort.

While there is some limited truth to these conclusions above, the benefits of the minimum wage outweigh the costs. Eight studies conducted in the United States analyzed the “economy wide effect” of the minimum wage on prices using various statistical methods and periods of time. These studies found that a 10% increase to the minimum wage corresponded with a .02-2.16% increase in prices. Seven of the eight studies estimated that a 10% increase of the minimum wage lead to less than a .4% increase in prices. This means, that the increase in the minimum wage earners income substantially outweighs the increase in prices. These studies are reviewed and outlined in this peer-reviewed survey of the literature and its public working paper (Lemos 2006; Lemos 2008).

Why do increases in the minimum wage lead to only small increases in the cost of goods and services? I haven’t yet found any empirical literature explaining why, however I have a few potential explanations:

First, not 100% of the price of products or services is cost of labor. A significant portion of the price is profit to the business. This means that if the cost of labor increases, they would not necessarily automatically be forced to raise their prices or be forced to go out of business. In some circumstances, businesses have the ability to reallocate some of their profit to the increased costs of labor. However, this does not mean that they will do so by default. It is the interest of businesses to maximize their profit, not allow it to be diminished by rising wages. So, one option for the business is to increase their prices to maintain their profit margin. However, this is conditional to whether or not people are willing to pay that higher price for that product. If customers are willing to pay the higher price for that product, then the business will be able to raise the price of the product and maintain the same profit margins. If consumers are unwilling to pay the higher price, then the business must make another choice. They must either raise their prices which reduces their sales and subsequently their profit margins or keep their prices low and still maintain low profit margins.

Second, another portion of the price of products and services is material used to create that product. These materials sometimes are made out of the United States, which is unaffected by increases to the minimum wage. This means that a portion of the cost of the product would be unaffected by the minimum wage increase. Alternatively, if the materials were made in the United States but by workers that were already making more than the minimum wage, the cost of the materials may not increase because the workers may not be particularly effected by the minimum wage increase.

In short, the benefits of raising the minimum wage typically outweigh the costs. Increases to the minimum wage lead to substantially smaller increases to prices, providing minimum wage earners significantly more purchasing power.

Does the minimum wage lead to higher unemployment?

Short(ish) Answer: There is some disagreement among studies regarding the effects of increases to the minimum wage on employment. Some meta-analyses of studies on this topic indicate moderate effects on teenage/youth employment, some indicate no effect on teenage/youth employment. Other meta-analyses claim there are smaller negative effects on aggregate employment, while other meta-analyses claim there are near zero effect on aggregate employment. As a whole, the meta-analyses did not seem concerned with large negative employment effects due to increases in the minimum wage. The majority of the meta-analyses did argue that employment sub-groups such as part-time workers, teens/youth, and restaurant workers, would be more negatively impacted than the the general population of workers. None of the meta-analyses claimed that the limited negative effects on employment outweigh the benefits of increasing the minimum wage. They only advocated that public policy should take into consideration nuanced changes to employment when proposing minimum wage increases, especially particular employment subgroups.

Long Answer: Another common concern with raising the minimum wage is that it may increase the unemployment rate. The logic is that if the minimum wage is increased, the business’ labor costs increase, therefore the employer must either reduce the number of workers employed or reduce the numbers of hours the workers work. This concept dominated the field of economics for several decades following the introduction of the minimum wage. The economic literature was in strong agreement that increases to the minimum wage had negative effects on employment. It is important to note that the majority of the literature focused only teen employment, which is only a small fraction of aggregate (total) employment.

However, in 1981, the Reagan administration froze the nominal minimum wage for 9 years, leading to a steady decrease in the real minimum wage. As a result many states rose the minimum wage at the state level to compensate. This created important variation in the minimum wage across states and throughout time thereby creating the conditions for new opportunities for research. In 1995, David Card and Alan Krueger created a study studying these new across state and time variations in the minimum wage and found surprising results. They found negligible, near zero effects of increases of the the minimum wage on employment. In fact, in some cases they witnessed positive effects on employment. While this study was groundbreaking, it was only one study (Card and Krueger 1995a).

That same year, Card and Krueger published a meta-analysis of previous studies published on the minimum wage. In this study, they found another groundbreaking result. Their statistical analyses indicated that the previous literature was subject to publication bias. This means that studies that found no statistically significant effect of minimum wage on employment were less likely to be published than studies with results that were statistically significant. This result was an over-representation of studies that showed statistical significance which typically favored negative effects on employment. This helped explain why their study disagreed with a significant amount of the literature (Card and Krueger 1995b).

However, David Neumark and William Wallscher in a 1997 study found the concern regarding publishing bias dismissible (Card and Krueger 1997). They claim that they found similar negative results with studies that did not indicate publishing bias. In a later meta-analysis, they concluded that two-thirds of their studies indicated a negative effect employment, mostly focused on teen and youth unemployment (Card and Krueger 2007). A 2016 study conducted another meta-analysis looking at more recent literature and found a moderate level of publication bias. That being said, they found a smaller negative effect on employment (Wolfson and Belman 2006).

In 1998, the United Kingdom implemented their national minimum wage. This created an opportunity to study the effect of a sharp increase in the minimum wage. A meta analysis conducted in 2017 found no statistically significant effect of increases of the minimum wage on aggregate employment in the U.K. Additionally, they found no publication bias across the studies included in the meta-analysis. They did note that among sub-groups such as part-time workers and certain labor market groups, increases in the minimum wage seem to have a negative effect on unemployment (Hafner et al. 2017).

In short, it appears that the effects of increases to the minimum wage on employment lies somewhere between no effect at all and small effects on aggregate employment with larger effects on some sub-groups of workers, such as part-time, youth/teen, and restaurant workers. The meta-analyses did not argue that the potential negative effects on employment would outweigh the benefits of increasing the minimum wage. Instead, the advocated taking into consideration the nuanced effects to employment when implementing different minimum wage policies.

Minimum wage workers are mostly high school and college students. They don’t need $15 an hour!”

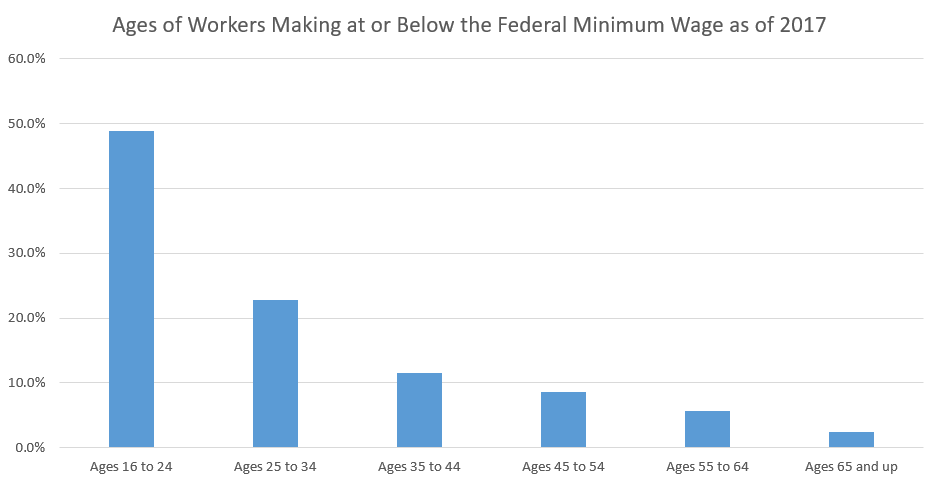

The first problem with this argument is that the majority of minimum wage workers are not high school students or college students. According the the Bureau of Labor Statistics as of 2017, about 49% of workers that make at or below minimum wage are between the ages of 16 to 24. That means that about the other 51% of minimum wage earners are 25 and older. See the chart below for more specifics.

This puts the average minimum wage earner in their early 30s. So, raising the minimum wage isn’t just a matter of giving high school and college students a little extra spending money. This also means giving people who are grown adults who likely have kids and family to support and bills to pay.

“I am alright with raising the minimum wage but $15 an hour is too high!”

The claim that “$15 an hour is too high” is subjective. It depends on what criteria is being used to define as too high. My response to people who make this claim is “Why is it too high? What is your preferred minimum wage rate? What makes it the correct rate?”. Often times their counter-response is “$15 an hour is over double the current federal minimum wage rate and almost double Illinois’ current minimum wage rate! I could understand maybe raising it to $9 or $10 an hour, but doubling it is too high”. Well, if a historical perspective is used, it is more clear that a $15 minimum wage implemented by 2025 isn’t as dramatic of an increase as many people think it is. I will demonstrate this by using Illinois as an example.

(Red Line = Real Federal Minimum Wage (in 2017 $, using CPI-U), Pink Line = Real Federal Minimum Wage + Real Illinois Minimum Wage Exceeding the Real Federal Minimum Wage (in 2017 $, using CPI-U-RS), Grey Line = Nominal Federal Minimum Wage + Nominal Illinois Minimum Wage Exceeding the Nominal Federal Minimum Wage (in current $). Nominal minimum wage data is from the U.S. Department of Labor and Illinois Department of Labor . Inflation data (CPI-U) is from Bureau of Labor Statistics with nominal minimum wage to calculate the real minimum wage (in 2017 $, using CPI-U). State minimum wages only apply if they are above the federal minimum wage. From the time the Illinois minimum wage was instituted to 2003, the Illinois minimum wage was lower than the federal minimum wage. From 2004 to now, the Illinois minimum wage has been higher than the federal minimum wage.

The graph above shows the history of the nominal and real minimum wage in Illinois. I also added the future minimum wage increases that just passed in Illinois, incrementally increasing it’s minimum wage to $15 an hour. However, by 2025, inflation will have changed the actual value of $15 an hour. Using the average inflation rates for the past 15 years, I adjusted the 2020 – 2025 minimum wage increases for inflation so they can be better compared historically. At 2.1% inflation every year until 2025, a $15 nominal minimum wage in 2025 would translate to real minimum wage of only $12.66 an hour (in 2017 dollars). The current real minimum wage for Illinois in 2019 is $7.89 (in 2017 dollars). This means that from 2019 to 2025, the Illinois’ real minimum wage would only increase by 62.3%. Compare that to the 85.2% increase in the real minimum wage in from 1949 to 1950 or the 119.7% increase in the real minimum wage from 1949 to 1956. Given this historical context, I believe the increase to the nominal rate of $15 by 2025 and the 62.3% increase in Illinois’ real minimum wage does not seem quite as dramatic or unrealistic as many are lead to believe.

The graph below shows the United States minimum wage data instead of Illinois’. Note that they adjust for inflation using CPI-U-RS in 2018, which is why the numbers are slightly different.

Double click the graph below to activate the interactive data visualization.

Does the minimum wage reduce income inequality?

Since the minimum wage increases the amount businesses must pay their employees per hour, this increases workers take home pay. This decreases the difference between working class’ share of income and the business owners, thereby modestly decreasing income inequality (Autor et al. 2016; DiNardo et al. 1996; Volscho 2005).

Do increases to the minimum wage lead to higher wages for non-minimum wage workers?

Research shows that workers who make above the minimum wage before the increase tend to make more than the minimum wage after the increase as well. When the proposed minimum wage rate is implemented, the workers who already made more than that proposed rate tend to see an increase in wages as well. This is referred to as the spillover effect. These increases, however, tend to be modest (Campolieti 2015; Dittrich et al 2014; Katz and Krueger 1992).

Well, if raising the minimum wage is so good, why not raise it to $100 an hour?

Like many phenomena, social and economic policy have costs and benefits. When modifying policy, likely the proportion of the costs and benefits will change. The goal is to find the “optimal” amount to maximize the pros with the least amount of cons possible. The problem is that knowing all the possible pros and cons of increasing the minimum wage and then quantitatively determining the optimal amount is not simple. There isn’t a consensus on how to calculate the optimal rate.

But there is pretty strong consensus that very extreme increases into the minimum wage would lead to large increases in unemployment, inflation, and other negative consequences. Considering that, I would categorize an immediate, over 1000% increase in the minimum wage to $100 an hour as a very extreme increase.

↑Less↑

Comments ( 0 )